MY LIFELONG INVOLVEMENT IN AFRICAN INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES

The history of the printed word in Kenya may be over four centuries old. It could be traced back to the Omani Arabs who ruled the Kenya Coast, on and off, before the coming of Vasco da Gama in 1498 to as late as 1867. They traded in gold, ivory, and slaves, making regular caravans into the interior in search of these commodities.

The Portuguese overthrew the Omanis in 1505 and were themselves later overthrown by European powers:

Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and others. The ‘Scramble for Africa’, in reality, was between 1881-1914. European explorers, missionaries, settlers, and colonizers, in that order, started arriving at the Kenya Coast from the the second part of the 19th century.

The missionaries regarded the Kiswahili language as adulterated by Islam and too ‘secular’ to be entrusted with Christian messages from the Holy Bible. So they settled among the local tribes, learned their languages, formed local language translation committees, harmonized orthographies as best they could and translated the bible and hymn book into these languages to facilitate their work. If they had elected to translate the bible into Kiswahili, as the Germans did for Tanzania, Kenya would have ended up a more homogeneous society than it is today.

In the case of the Luhya communities of Western Kenya, for example, where there are over seventeen dialects, they chose to work in Kimaragoli, Kinyore, and Kiwanga and imposed these languages on the rest of the other tribes. The traditional animosity between the Maragoli and the Bukusu can be traced to this beginning. The Bukusus may have been larger in numbers but they were ‘forced’ to use the Maragoli bible and hymn book until recently. Learners were required to select one of these languages for their early education from Std1 – 3 which, in those days, was taught entirely in mother tongue.

When one remembers the dominance of Kiswahili (an African language that has absorbed many Arabic words), and the preponderance of Arabic classical narratives such as ‘Hekaya za Abunwasi’’ ‘Alfulela-u-lela’, ‘The Arab and the camel’, etc, and proverbs such as ‘Usikate kanzu kabla ya mtoto hajazaliwa, ‘Asante ya punda ni mateke, etc; and the rich repertoire of Arabic and Muslim language and cultural artifacts at the Coast, one is left with no alternative but to accept this view. ‘Watu wa bara’ was a derogatory term used to separate the ‘Wastarabu’ and the uncivilized indigenous folks from upcountry.

The next milestone in the development of local languages was in 1948 when the East Africa High Commission was formed and following the recommendations of the Elspeth Huxley Report, the East African Literature Bureau, (EALB) was set up to publish books in local languages for local use. I have covered the work of Charles Richards in detail in one of my publications and will not return to it here. Suffice it to say EALB could have done more but was riddled with systemic inefficiency and was generally underfunded. When the East African Community was dismantled in 1977, each of the 3 countries set up their own publishing units. The Kenya Literature Bureau (KLB) was established immediately afterward as a state publishing firm under a new mandate. It would no longer exclusively publish in local languages and was now perceived as a commercial outfit.

Laying the Foundation

I graduated from the University of Nairobi with a First Class Honours degree in Literature and Philosophy in 1972 and immediately took up a job as TV Producer with Voice of Kenya Television, and also enrolled for a Master’s degree in Philosophy. After one term, I abandoned the Philosophy department and sought assistance from my Literature Professor, Andrew Gurr who arranged for me to take up a ‘temporary’ job at Heinemann Publishers, Nairobi while he tried to secure an overseas scholarship for me, But, soon after joining Heinemann, I was seconded to Head Office in London where I worked for 9 months and upon my return to Nairobi was promoted to the position of Publishing Manager, taking over from David Hill in May, 1974.

Two years later, I was promoted to the position of Managing Director, taking over from Bob Markham under circumstances which found me unprepared, but which I won’t go into here. The company arranged for me to buy a house in Lavington, which was a major shift from Nairobi West where I lived. With these fast developments, I said goodbye to my dreams of further education and concentrated on my work. I was now comfortable; mentally, physically and financially.

At the tender age of 30, I was sitting on top of a multinational, The Head Office had said they would allow me space to operate freely, as long as I returned a profit at the end of the day. I decided to invest in people, to set up a formidable editorial department that would make the right choices and filled it with First Class brains, such as Laban Erapu, Paul Njoroge, Simon Gikandi, Jimmi Makotsi, Barrack Muluka, Nazi Kivutha, Lillian Dhahabu, Leteipa ole Sunkuli, to name but a few. I backed these people with a host of experienced external readers, editors and advisors. Names such as Philippa de Cuir, Rodney Nesbitt, Kimani Njogu, Kivutha Kibwana, Senda wa Kwayera, Okoth Okombo, Wahome Mutahi, Chacha Nyaigoti Chacha, Esther Kantai, Ashiq Hussain, were on my list. A host of new authors were brought on board and many publishing opportunities and innovative ideas were created at our weekly Wednesday meetings, including publication of new textbooks, academic and general books, students’ guides to prescribed set books, publishing in Kiswahili and in mother tongues. Most of the books were published locally, but some, such as AWS manuscripts, were sent to London for publication.

My personal involvement

My dalliance with African languages is as old as my publishing career. When I joined Heinemann Nairobi in 1972 as Editor, I found three books in galley proofs, waiting to be produced: ‘Mtawa Mweusi’ (Kiswahili translation of Ngugi’s Black Hermit and ‘Usilie Mpenzi Wangu’, Weep Not, Child,‘ Kivuli Cha Mauti’, (Dying in the Sun), by Peter Palangyo. I had to summon my best Kiswahili knowledge to see these books through to finished copies. The company had earlier published ‘Ebb’yenda Bisasika‘ (Things Fall Apart) in Luganda and, although the book had been prescribed as a textbook by the Ministry of Education in Kampala, sales had been poor. I continued to issue Kiswahili translations of selected titles in the African Writers Series even though, again, sales were not always that brilliant.

In 1974, I was appointed a jury member on the Founding Committee of the Noma Award for Publishing in Africa. The first winner of the prize was the Senegalese feminist writer Mariama Baâ, and I expressed interest on behalf of Heinemann for translation rights into English and Kiswahili of her novel Solong a Letter. The second-year prize went to Meshack Asare’s, The Brassman’s Secret, although my own preference had been Myombekere na Bugonoka. Na Ntulanalwo na Bulibwali, a Tanzanian tome that detailed the day-to-day life and living of the Bakerewe people of Ukerewe Islands. My detailed report recommending Aniceti Kitereza for the prize may still be in the archives of that Award.

When Hans Zell, Convenor of the Award, saw my deep interest and commitment to African local languages, he recommended me to UNESCO who then invited me to a conference in Alma-ata, USSR in 1976. I presented a paper entitled “Publishing in a Multi-Lingual situation: The Kenya Case” to much acclaim, and this was published in the African Book Publishing Record (ABPR), 1977. I became a regular guest of UNESCO at their various seminars and conferences and even managed to write a monograph for them by the title Books and Reading in Kenya, which was published under their Books and Reading Series (1982).

At the National Level

My Involvement after 1976 was tied up with local events in Kenya. The first was a conference held at Nairobi School, which revolutionized the teaching of Literature in Kenyan secondary schools; and a parallel one was the change taking place in the Literature department at the University of Nairobi, engineered by Ngugi and his African colleagues. The second was my close association with Ngugi himself who had been my teacher at Nairobi University, and whom I was now made to handle on behalf of Heinemann London.

My publishing relationship with Ngugi has been well documented and I won’t highlight it here. Suffice it to say I was critical to Ngugi’s publishing output in the Gikuyu language and in English and Kiswahili translation between 1975 to 1982, the year he went into exile. We had agreed that every book published by him would immediately be followed by a translation in what he termed ‘a conversation between languages’. Within this period, I published The Trial of Dedan Kimathi (Mzalendo Kimathi), Ngahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), and Caitani Mutharaba-ini (Devil on the Cross). Because of the circumstances of the time, these three sold in very large quantities and I was able to reprint several times up to the time when they were ‘banned’.

In 1979, I embarked on an ambitious project to publish textbooks in Kiswahili in order to strengthen the teaching of Kiswahili in both primary and secondary schools. Kiswahili was an examinable subject at the secondary level but there were no course books and most schools chose to ignore it, using its period to teach other subjects instead. By the end of 1980, I had completed a full secondary course and the first three books of Masomo ya Msingi, the primary course, plus teachers’ guides. The sales were sluggish at first, but I soldiered on, completing the entire course in 1982, the same year President Moi decreed that Kiswahili should be taught as a compulsory subject at all levels.

There was no curriculum, no preparation, nothing except my adventurous course. So huge were the sales that, at one stage, this course alone accounted for 85% of our entire turnover. It also helped to cushion me against the adverse effects of parting with Heinemann London in 1986-1992, a process, which had started well but had ended in acrimony. Around the same time, I commissioned the writing of children’s books in mother tongues. I challenged already successful writers in English, such as Ngugi, Grace Ogot, Asenath Odaga, David Maillu and Francis Imbuga, among others, to write. The above mentioned did submit manuscripts, and the first mother-tongue children’s books started rolling out of EAEP in 1982.

Again, sales were poor because, admittedly, the quality was wanting as local editors, printers and designers were not capable of handling the special features that go into children’s books publishing; special paper that can withstand handling, full-color illustrations, design and printing, and the project, which I eventually abandoned, needed a readership outside the textbook market to be sustainable, of which there was very little.

Paradoxically, when I published English translations of these same readers, sales improved considerably. I also invested in Orature. I realized that the old generation was fast disappearing. So I commissioned people to carry out research among their communities. I would publish their works under the Oral Literature of Kenya Series, which I had created for that purpose. The text would, by and large, be in English but the songs and any other special features would be preserved in the mother tongue. I was able to release books in the following language communities: Gikuyu, Dholuo, Maasai, Kalenjin. Many of these books are still being used in the teaching of Orature today, especially at the university level.

The books are in a rough and ready form and my hope is that one day, the company will use them to produce illustrated coffee table editions such as I see in local bookshops from foreign publishers.

There is an international group of researchers, clustered around Professor Gayatri Spivak of

Sample Text

Musician Stevie Wonder (centre) poses with the Ngugis (left) and Congressman John Lewis. On the right in Mukoma wa Ngugi.

Early this week, the American city of New Haven, Connecticut, was downcast before a drizzle melted, as a crowd of 1,000 roared at the indoor arena to appreciate the eight elderly men and women about to be crowned.

That moment, now frozen in an official graduation picture that has been widely circulated, features two black men on

The man on the left is John Lewis, the American Congressman and legendary civil rights activist who worked with Martin Luther King Jnr; the man on the right is Prof Ngugi wa Thiong’o, the celebrated Kenyan writer and cultural theorist.

This was at Yale University when the two joined a pantheon of six others to receive honorary doctorates in this year’s commencement. Other famous Americans in the line-up that Kenyans might be familiar with include megastar Stevie Wonder and former US Secretary of State John Kerry.

Wonder danced and sang along as the university band gave a rendition of his hit, I Wish, while Yale University president Peter Salovey used Wonder’s own lyrics in the citation: his degree was “signed, sealed, delivered, it’s yours.”

Ngugi’s citation read: “Author, playwright, activist, and scholar, you have shown us the power of words to change the world. You have written in English and in your Kenyan language, Gikuyu; you have worked in prison cells and in exile, and you have survived assassination attempts — all to bring attention to the plight of ordinary people in Kenya and around the world.

“Brave wordsmith, for breaking down barriers, for showing us the potential of literature to incite change and promote justice, for helping us decolonise our minds and open them to new ideas, we are privileged to award you this degree of Doctor of Letters.”

This is Ngugi’s 12th honorary doctorate — having received others from universities in the US, Europe and Africa. KCA University made history last year when it became the first Kenyan institution to accord the author with a similar honour.

“It was a particularly great honour because it came from home,” Ngugi said of the recognition from KCA.

The award from Yale, one of the top universities in the world, is somewhat bittersweet; it reminds of the scant praise that Ngugi receives from home, even though his pioneering work has been entrenched in Kenya and replicated elsewhere in the world.

Dubbed the Nairobi revolution, the campaign in the late 1960s to situate the study of African literature and its diaspora at the core of what was then the Department of English at the University of Nairobi is now a well-grounded literary theory in post-colonial studies.

Ngugi’s subsequent declaration in the early 1980s that he would stop writing in English to embrace his first language, Gikuyu, has prompted indigenisation efforts from as far places as Hawaii and New Zealand and South Africa, where writers and cultural proponents are evaluating the legacies of oppression and segregation in knowledge production.

“Decolonisation is a message that’s resonating with many people across Africa,” Ngugi said in a recent conversation, revealing that some 2,500 people showed up for a lecture in Johannesburg South Africa in March.

South African universities have been grappling with the legacy of Apartheid, with some organising protests against what they see as symbols of their oppressive past.

During last month’s Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, Ngugi was asked by the American critic, Rebecca Carroll, whether he had managed to “decolonise” himself, invoking the title of his treatise: Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature.

“I’m still trying,” Ngugi admitted, no doubt weighed down by the recognition that he has not published often in Gikuyu, despite his earlier “farewell to English.”

Columbia University, USA, and we are together exploring the possibility of exploiting the audial and phonetic aspects of Africa languages to enable them to play a greater role and yet bypass the written form. If this experiment succeeds, it will provide a bridge between the oral and written forms of African literature. I served, un-interrupted as Chairman of the Kenya Publishers Association for 10 years between the period 1982-1992, at the most tumultuous period of this Nation and the association’s history. It was fraught with all sorts of risks, which I managed to navigate and still remain in the ‘good’ books of my publishing colleagues and, more importantly, the government.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

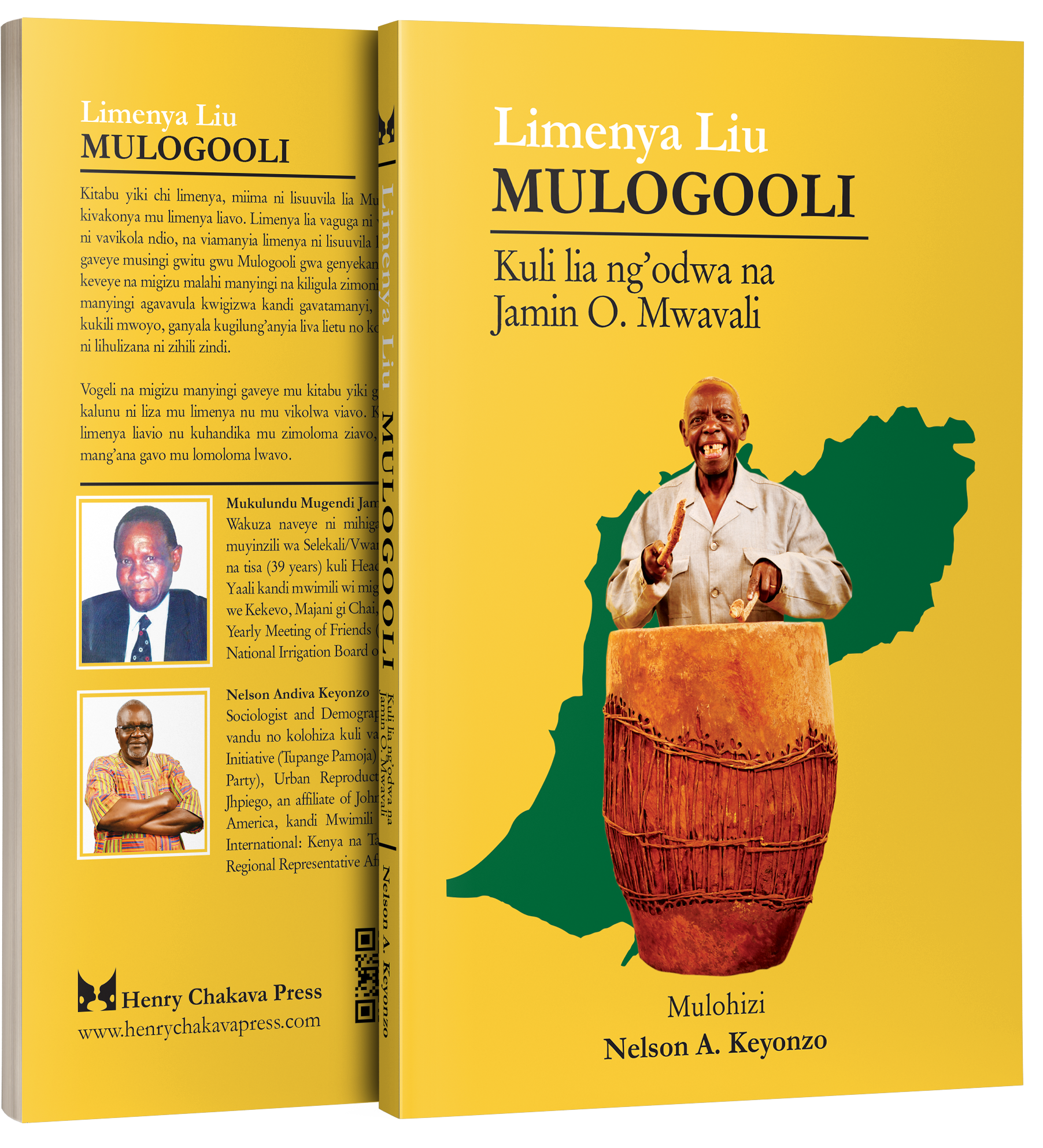

So much for my publishing. My corporate social responsibility involved many other things, such as the Maragoli Cultural Festival which I created in 1979, and I chaired for the first 10 years of its existence. President Moi attended it no less than 3 times during my tenure, and made important policy statements. In 1982, he decreed that ALL communities in the country must hold cultural festivals on 26th December, which was the date of ours. Thus, the Maragoli Cultural Festival, now in its 40th year, can claim to be the Mother of all cultural festivals in Kenya. This initiative earned me a Head of State Commendation (HSC), in 1992.

At the Continental Level

At the continental level, I was instrumental in the formation of APNET and helped secure SIDA funding for it. The late Chief Victor Nwankwo was elected first Chairman and I was given the No.2 position of Treasurer. In addition, being the most experienced, I was elected Chairman of IPI (international Publishing Institute), the training wing of APNET. During this period, and in this position, I traversed the whole of Africa, from Egypt to South Africa, Sudan to Guinea, altogether covering 32 countries in 10 years, attending conferences, administering and training on behalf of APNET. I was involved in most of the start-ups of this period, the most remarkable being James Tumusiime’s Fountain

Publishers of Uganda.

Also with SIDA as the main partner, I was able to launch the East African Book Development Association (EABDA) to train and encourage East African Publishers to venture out and grow. Again, I led it through its first 10 years as Founding Chairman, making regular supervisory visits to Kampala and Dar es Salaam. EABDA also sponsored and encouraged the formation of National Book Development Councils, whose forte included the strengthening of indigenous publishing institutions, and promoting African languages and cultures.

Following UNESCO guidelines, I single-handedly registered the National Book Development Council of Kenya (NBDC-K) and constructed a board consisting of heads of book organizations from Publishers, Booksellers, Printers, Librarians, as recommended by UNESCO. I also invited government departments such as the National Commission to UNESCO, The Ministry of Education, the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development, (KICD), the Department of Culture, the Department of Adult Education, etc.

Altogether, I put together a Board of about 15 people and with the help of Anita Theorell, Director of Culture and Media and her able assistant Per Knutson, received funding from SIDA and other sources. CODE Canada Under Scott Walter came on board, and other small unilateral donors followed suit. I served as Chairman for the first 10 years and retired only after I judged the project sustainable. Under new leadership, the Council lost the Swedish funding, but CODE still continues with them.

The first 10 years under my leadership were aggressive and full of action within the country and the East Africa region. NBDC-K has done some good work and continues to generate literacy materials for the Abagusii and the Maa people of Kenya and administers the Burt Award for Publishing in Africa. Last year, it launched a Children’s book fair which seems to have found a good niche’. I am proud that, twenty years after inception, the Council continues to be relevant and to complement the efforts of the Kenyan book community. Throughout, due emphasis has been given to indigenous writing and publishing.

My firm, at my insistence, has developed a vibrant local language publishing program. In the new competency-based curriculum just released, they were the only ones to submit complete courses in local languages, all of which were approved for use in Kenya primary schools. They have also released 38 titles in digital format in Icinyanja and Icibemba for the Zambian market and uploaded them on the World Reader platform. It remains to be seen whether or not these books will be bought and used. Experiments in publishing in regional indigenous languages such as Luganda, Kinyarwanda, Cinyanja (Malawi), Icibemba (Zambia), have only been partially successful in spite of the fact that these books have been approved as school texts and appear on official tender documents. Yet our publishing in Kiswahili has been a roaring success story from the beginning with sales in millions of shillings. In fact, I would say 55% of our total publishing turnover is derived from Kiswahili language publishing. That is the paradox.

At the International Level

On the international front, I enrolled KPA as a member of the International Publishers Association (IPA) and served on its Censorship and copyright Committees. Sponsored largely by international donor and development agencies, I traveled to 30 different destinations outside Africa and presented over 50 papers around the world, a majority of which were later published in one form or the other. I was able to gain recognition by being declared the best publisher in Africa at the Zimbabwe International Book Fair in 2003, honored with a doctorate degree by Oxford Brookes University, United Kingdom, (2006) and declared a winner of the Prince Claus Award (2007) from The Netherlands. I also served on the Board of the African Books Collective from inception in 1986 – 2017 when I voluntarily retired after years of religiously trooping to Oxford University every year for the ABC annual Board meetings and AGM, with Walter Bgoya and Mary Jay as Chairman and CEO, respectively.

The most memorable of my many overseas trips was to Vienna, Austria in 1988. I was invited by the International Booksellers Federation (IBF) to address a plenary session on the topic ‘Book Distribution in Africa’. At the closing ceremony, Micheal Zifcak, the Australian President of the Association, asked that every delegate be given one minute to say something in their mother tongue. Most of the speeches were in English, French and some European languages. I chose to speak, not in Kiswahili, but in Kimaragoli, my mother tongue. After my little ditty, Michael leaned over and whispered to me ‘ What a beautiful language.

It was like music to my ears’. I was over the moon. At the end of the dinner which was at Beethoven’s Den, we were all invited to a wine tasting competition underground. I was very good with wines those days and was able to beat the 100 delegates or so who participated in the competition to win the choice prize; two bottles of vintage wine, one white and one red. On the way back to the hotel, in a state of inebriation, I donated the two bottles to the bus driver who drove us back to the hotel, much to the consternation of my colleagues.

I woke up the following day at noon, with a stinging headache, having missed my train ride to the airport, for which a free ticket had been provided. I jumped into a taxi to the airport but it was too late. I found the Counter closing, but Swissair were sympathetic enough to book me on Austrian Airways two hours later, warning that the connection to Nairobi might be tight.

When we landed in Zurich, I found a car waiting for me on the runway. I was whisked, ambulance style, across Zurich Airport to the waiting plane and was, in fact, one of the first to board. That night I never touched alcohol in spite of all provocation from the flight attendants in business class. It took me three days to recover from this whole experience.

Conclusion

Research carried out internationally by linguists has scientifically proved that learners weaned in mother tongue in the early* years of their education have a better grasp of concepts in other subjects (and languages) later in life.

Mother tongues also confer cultural pride, belonging and awareness to the user. However, in the case of Africa, these languages were stigmatized, declared socially inferior, and foreign languages such as English, French, and Spanish marketed as languages of immense opportunities and development.

The time has come for African languages to take their rightful place in society. Digital publishing, for example, can provide a leap, and this can be achieved through partnerships with international agencies such as World Reader mentioned above. Let me attempt, by way of concluding, to make some observations as to the obstacles facing local languages publishing and use. These languages are generally perceived to be good for verbal communication, and no commercial value. Some don’t even have written or harmonized orthographies, with the same word appearing differently even within the same text, hence difficult to read even by the most literate. The Holy Bible is a case in point and is still, in most cases, available in orthographies formulated by the original missionaries.

Indigenous languages are not considered important for learning and educational purposes. Often times the period set aside for teaching or learning local languages is used to teach other subjects such as Math or English. These languages are not taken seriously even though politicians exploit them effectively during election campaigns. Publishers don’t take them seriously either, arguing that they are a hard sell. They will normally produce them to lower standards, poor paper, poor design, and smudgy inking, no color, and few illustrations. Print runs are usually small, complicating the pricing process. Their marketing poses new challenges as language groups may be concentrated in one area or scattered all over and difficult to specifically target.

Print quantities are generally nonviable and even when some titles appear on government tenders, they don’t get ordered, or are ordered in very small quantities. Finally, indigenous books suffer from the same problems encountered in mainstream publishing: poor book reading and book-buying habits, poverty that makes it hard for people to afford to buy books, a poor reading environment with few bookshops and libraries, lack of electricity in schools and homes, making it impossible to read at night, etc.

Attempts to deal with these problems have been, by and large, unsuccessful but one can say, African countries, with assistance from donors and development partners, are beginning to take the book seriously if one can go by the various international book schemes in operation today. The Kenya government is called upon to strictly enforce policies relating to the teaching and learning of mother tongues in the early years of primary education and to sensitize the public on the cultural and social benefits of this approach as it instills pride and confidence in the learner. Kenyan publishers are advised to be more enterprising and to invest some of the profits they are currently making from these schemes into the neglected areas of general and indigenous languages publishing.

Sample Text

Musician Stevie Wonder (centre) poses with the Ngugis (left) and Congressman John Lewis. On the right in Mukoma wa Ngugi.

Early this week, the American city of New Haven, Connecticut, was downcast before a drizzle melted, as a crowd of 1,000 roared at the indoor arena to appreciate the eight elderly men and women about to be crowned.

That moment, now frozen in an official graduation picture that has been widely circulated, features two black men on

The man on the left is John Lewis, the American Congressman and legendary civil rights activist who worked with Martin Luther King Jnr; the man on the right is Prof Ngugi wa Thiong’o, the celebrated Kenyan writer and cultural theorist.

This was at Yale University when the two joined a pantheon of six others to receive honorary doctorates in this year’s commencement. Other famous Americans in the line-up that Kenyans might be familiar with include megastar Stevie Wonder and former US Secretary of State John Kerry.

Wonder danced and sang along as the university band gave a rendition of his hit, I Wish, while Yale University president Peter Salovey used Wonder’s own lyrics in the citation: his degree was “signed, sealed, delivered, it’s yours.”

Ngugi’s citation read: “Author, playwright, activist, and scholar, you have shown us the power of words to change the world. You have written in English and in your Kenyan language, Gikuyu; you have worked in prison cells and in exile, and you have survived assassination attempts — all to bring attention to the plight of ordinary people in Kenya and around the world.

“Brave wordsmith, for breaking down barriers, for showing us the potential of literature to incite change and promote justice, for helping us decolonise our minds and open them to new ideas, we are privileged to award you this degree of Doctor of Letters.”

This is Ngugi’s 12th honorary doctorate — having received others from universities in the US, Europe and Africa. KCA University made history last year when it became the first Kenyan institution to accord the author with a similar honour.

“It was a particularly great honour because it came from home,” Ngugi said of the recognition from KCA.

The award from Yale, one of the top universities in the world, is somewhat bittersweet; it reminds of the scant praise that Ngugi receives from home, even though his pioneering work has been entrenched in Kenya and replicated elsewhere in the world.

Dubbed the Nairobi revolution, the campaign in the late 1960s to situate the study of African literature and its diaspora at the core of what was then the Department of English at the University of Nairobi is now a well-grounded literary theory in post-colonial studies.

Ngugi’s subsequent declaration in the early 1980s that he would stop writing in English to embrace his first language, Gikuyu, has prompted indigenisation efforts from as far places as Hawaii and New Zealand and South Africa, where writers and cultural proponents are evaluating the legacies of oppression and segregation in knowledge production.

“Decolonisation is a message that’s resonating with many people across Africa,” Ngugi said in a recent conversation, revealing that some 2,500 people showed up for a lecture in Johannesburg South Africa in March.

South African universities have been grappling with the legacy of Apartheid, with some organising protests against what they see as symbols of their oppressive past.

During last month’s Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, Ngugi was asked by the American critic, Rebecca Carroll, whether he had managed to “decolonise” himself, invoking the title of his treatise: Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature.

“I’m still trying,” Ngugi admitted, no doubt weighed down by the recognition that he has not published often in Gikuyu, despite his earlier “farewell to English.”